It’s said that the first five minutes of any film are the most important - and that’s especially true of a James Bond film. While recent Bond movies have experimented with the classic formula, "Spectre’s" opening moments are ripped right out of 1962: a gun barrel, Monty Norman’s iconic riff, and the shot. A familiar calling card before our next adventure.

Once the credits start rolling, that feeling of familiarity only grows. After 24 movies, this sequence has become much a part of the Bond experience as his pithy quips and vodka martinis. They almost always feature the same iconic elements: a song, the silhouetted dancing girls, the explosions, the guns, and the man himself. But even with all those constraints, there’s still room for the title sequence’s designers to play around and stir in some fresh ideas.

“What’s interesting about the Bond titles is that you’re presenting things that people have seen before, and that’s what they want. They don’t want to see a title sequence that looks like it’s from another film,” says Framestore’s William Bartlett, who’s served as Visual Effects Supervisor on the titles for "Die Another Day," "Casino Royale," "Skyfall," and "Spectre." “The big challenge is how to present the imagery in a new way, that people feel is original.”

As a company, Framestore knows Bond title sequences inside-out. It's worked with director Daniel Kleinman to create the visual effects for almost all the titles since 1995's "Goldeneye," and the creative process for each sequence is roughly the same.

It begins with Kleinman reading the film’s script. He then approaches Framestore with some sketched out ideas for the titles. Then there’s some back-and-forth between the two, as Kleinman whittles down his concepts, and Framestore figures out how to make the most of any new technology that’s come out since the last film.

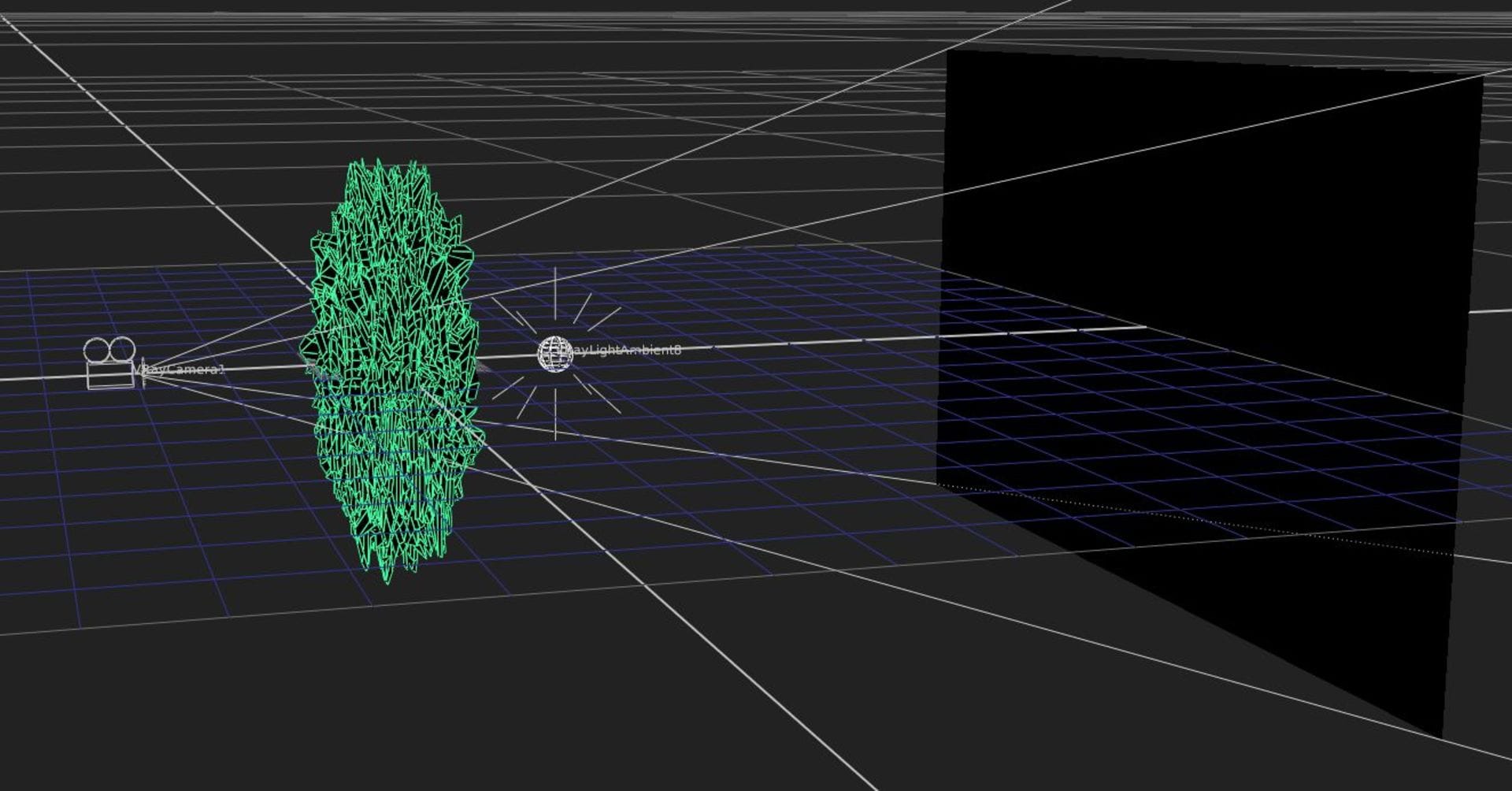

In Spectre’s case, it was a great time to try out Chaos Group’s V-Ray for Nuke. While Nuke is a mainstay of compositing, the introduction of V-Ray has added another creative element to the software. Effectively turning it into a tool which can now create beautiful imagery, as well as handle the nuts and bolts of complex composites.

Curious, Framestore began experimenting with the software to see how it could fit with the sequence. “We just mucked about with it a bit to see what we could do,” says Bartlett.

We never tried to do stuff that looked like 3D with V-Ray for Nuke. We wanted to use it as a compositor, but in a much more elaborate way with some of the new tools.”

William Bartlett, Framestore

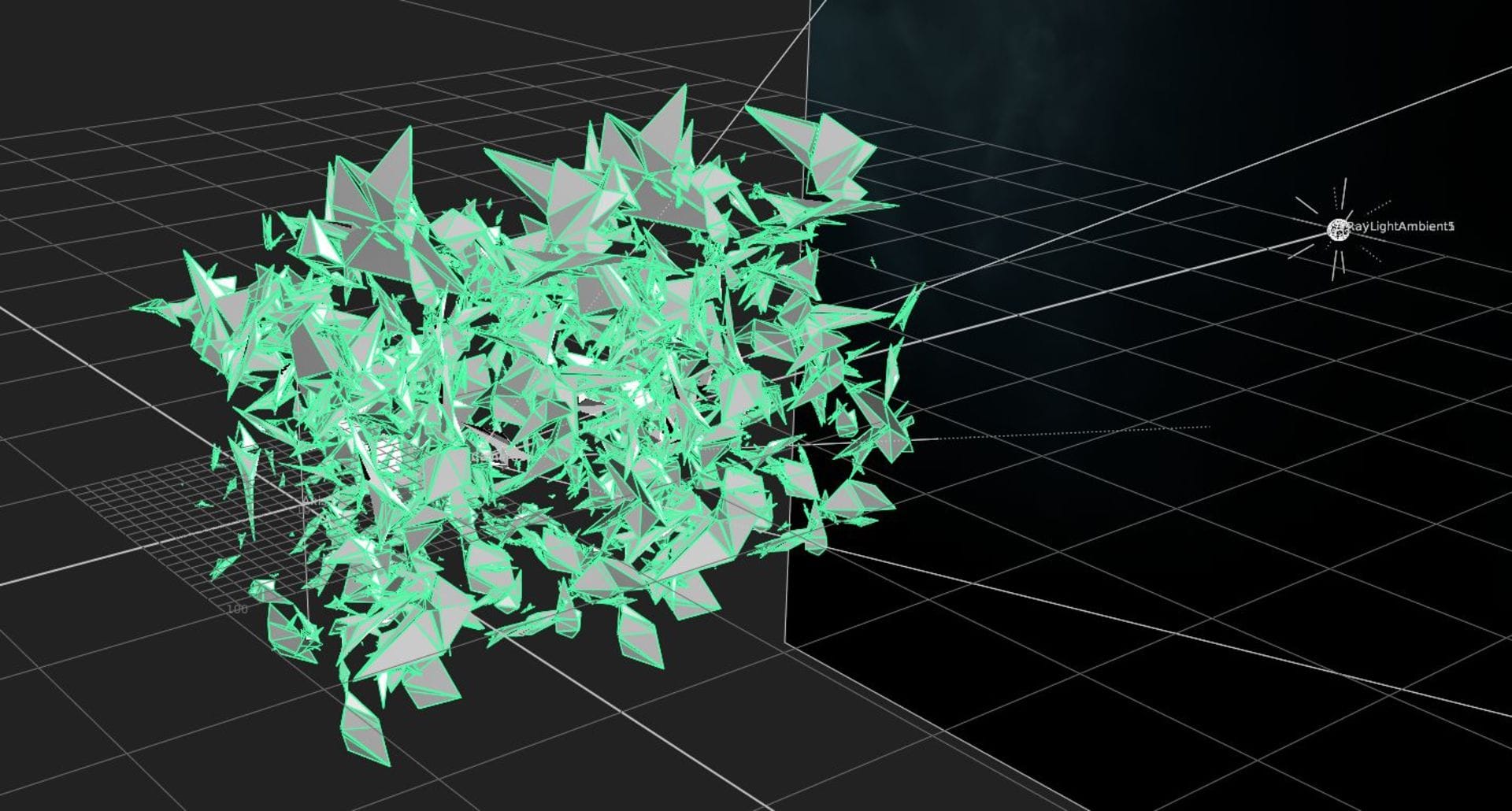

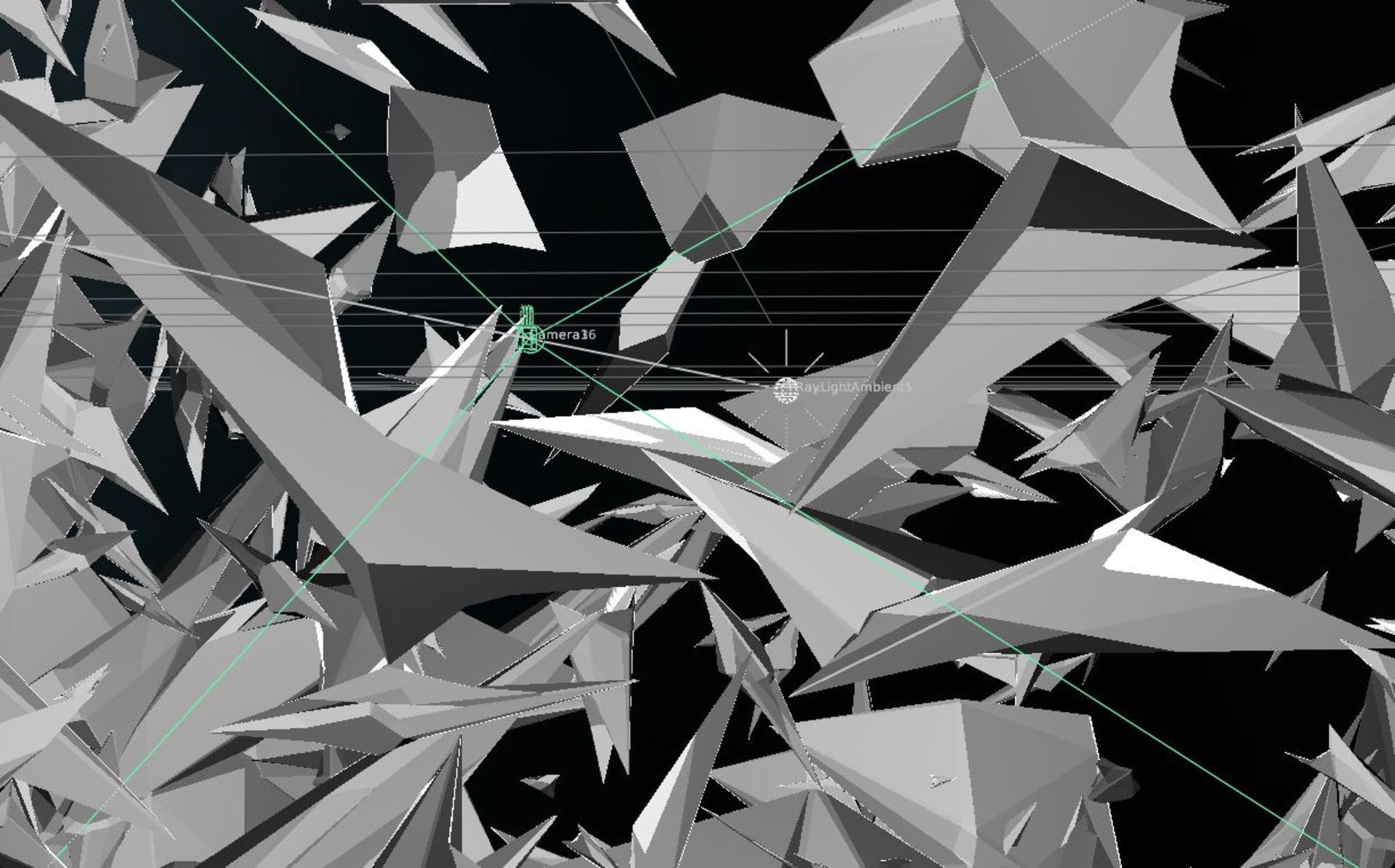

Initially the V-Ray for Nuke section of the credits was planned to be far more extravagant. Nuke expert and compositor Jesse Spielman creating dancing girls made of shattered glass, with textures tracking behind them. It was beautiful, and technically brilliant—but it simply didn’t fit with the tone of the overall sequence.

However, this experiment gave the team a better idea of how Nuke could be used in a far subtler, but more dramatic manner. The dancing girls were replaced with characters from Daniel Craig's previous outings as Bond. The faces of Raoul Silva (Javier Bardem) and Le Chiffre (Mads Mikkelsen) shatter like glass, while Vesper Lynd (Eva Green) and M (Judi Dench) appear in billowing waves of inky liquid. It's at once dreamlike and disturbing, and it provides a neat recap of Bond's past.

While the scene looks amazing, the crucial element was V-Ray for Nuke's ability to quickly churn out renders. “Iteration is the most important thing,” says Bartlett. “It’s a lot of little tiny changes that turn it from something that’s bland and not very good, into something that looks really interesting with a good flow and rhythm. You don’t want to get hung up on making a single frame look beautiful too early, it’s more important to get the way the images flow from one to another.”

In order to increase the speed of this iterative process, Spielman built a gizmo in Nuke with two render nodes: one for a faster, almost interactive render with low samples and raytracing gaps, and one for a far higher quality output. The low-quality renders were used for timings, locations, movements and framing, while rendering every fifth frame at high quality ensured that the more complex reflections and refractions were in all the right places.

By using V-Ray for Nuke for both lighting and compositing it effectively halved the workload of the final renders. “I realized that we were compressing two previously discrete steps into one,” says Spielman. “It was a change in thinking—I’m not used to letting the computer do that much math to get the final result.”

The merging of these steps marks a big change for the visual effects industry—lighters, compositors and modellers can now work together within one piece of software. And it’s definitely found a place in Framestore’s effects arsenal. “I can see us using it as a lookdev tool to give people an indication of what we’re doing,” says Bartlett. “Rather than it being a rubbish grayscale thing, we can attach a shader and render something with nicer shadows, but still at low quality.”

On the other hand, Bartlett is keen to let artists continue to experiment with it. “I think we could use it a bit like we did in Bond, where we creatively came up with images that you couldn’t do in Nuke on its own, and it’s not something you could do with 3D. Combining footage with more complicated shading and shadows is definitely another use for it. I think different artists will take it in different ways.”

Bartlett already has V-Ray for Nuke lined up for his next project: "SS-GB," which marks his debut as title sequence director. This six-part BBC drama, due to air in the UK early next year, already has a lot of Bond talent attached: As well as Framestore, it’s written by Bond scribes Neal Purvis and Robert Wade, and deals with Bond-ish espionage in a Nazi-conquered version of 1941 Britain.

“The title sequence is going to rely very heavily on V-Ray for Nuke, especially the shadows,” Bartlett says. “It’s another example of mucking about with the tools, coming up with interesting aesthetic languages, and finding things that look good that will tie into the sequence.”

Whether it’s Bond or a project on the horizon, Bartlett is hooked on what V-Ray for Nuke now offers professional artists. “It’s not like building a scene with a load of models and then doing some stuff with it,” says Bartlett. “You’ve got to time in the live-action footage, and you’ve got to grade it all in. If you tried to do all that stuff in a 3D package, the length of time it would take to do any variation would be so long that you would never have time to work into it. Without V-Ray for Nuke there’s simply not a way you could do it.”