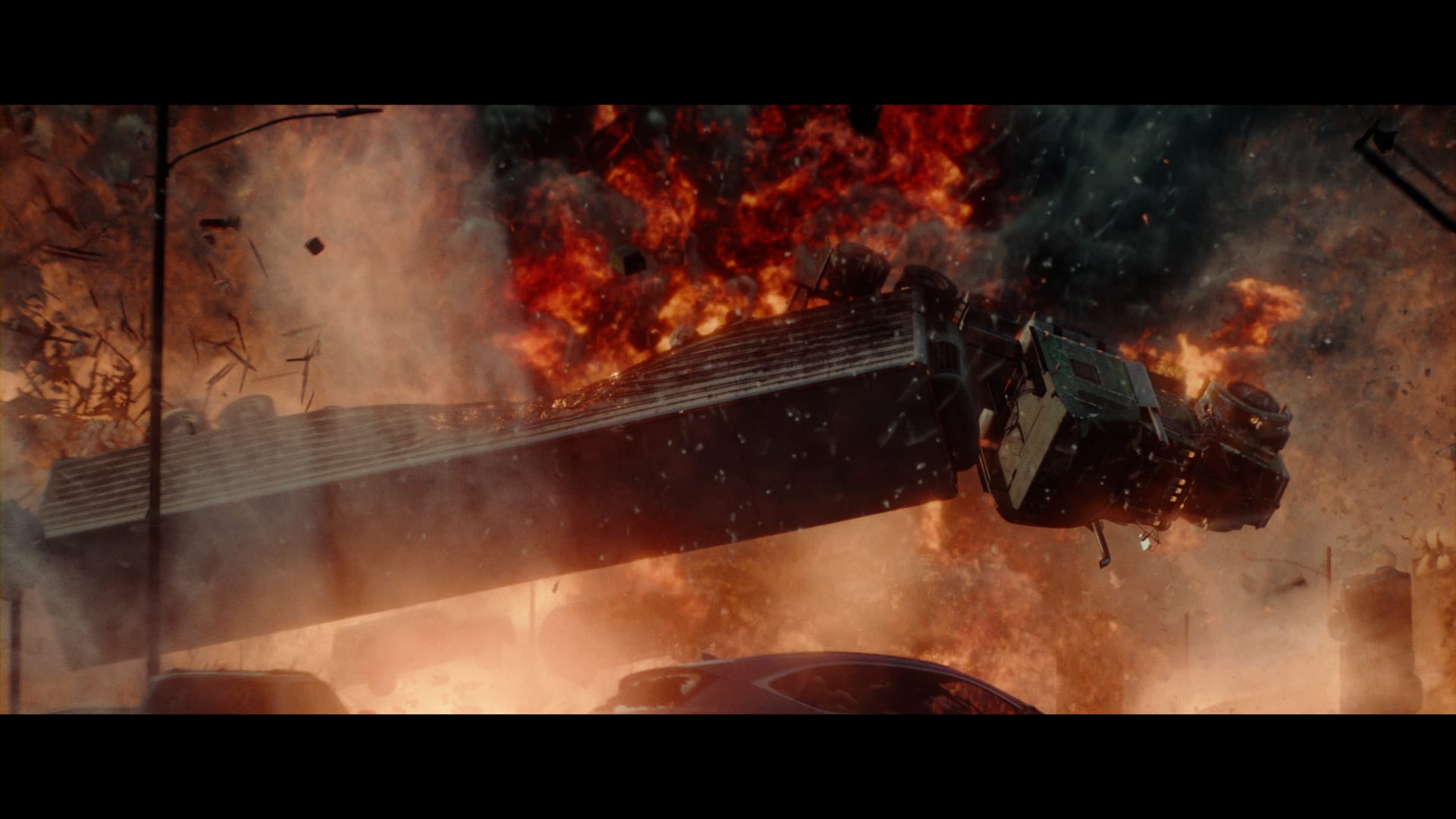

Roland Emmerich’s latest disaster flick includes a dramatic car chase through a ski resort. We talk to Scanline’s Mathew Giampa about how they did it.

Roland Emmerich’s ongoing quest to wreak havoc on the world has resulted in some of the best VFX in cinematic history — whether it’s blowing up the White House for Independence Day, flooding New York in The Day After Tomorrow, or fracturing Los Angeles for 2012.

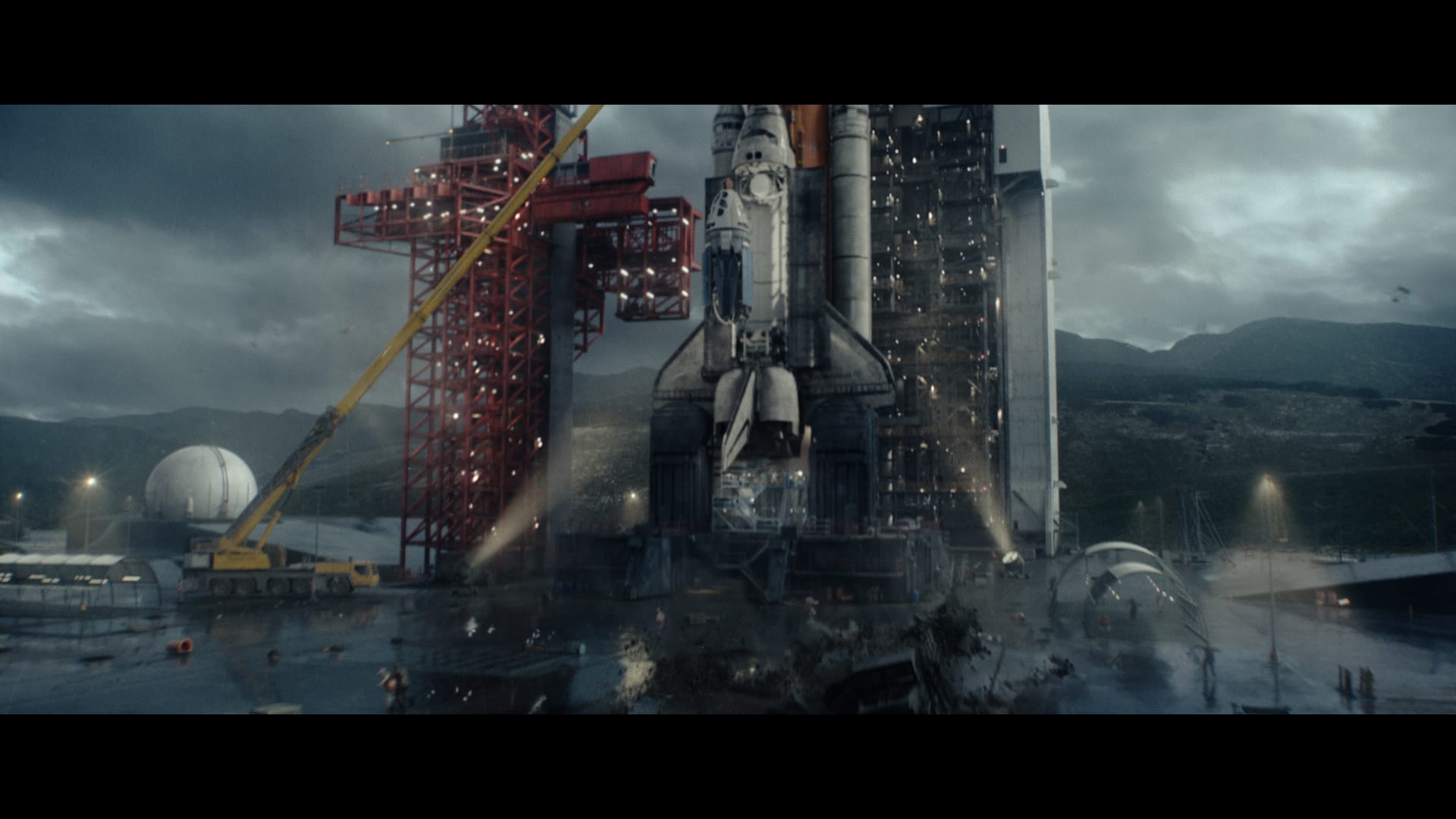

Having destroyed most of the known world on-screen, Emmerich seems to be looking for new and unusual places to obliterate in new and unusual ways. Case in point: Aspen, the Colorado ski-resort town in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, which is spectacularly pummeled by the moon’s gravitational pull in Moonfall, Emmerich’s latest.

Emmerich turned to regular partner-in-demolition Scanline VFX to provide entirely digital shots for the Aspen sequence. Here, VFX supervisor Mathew Giampa lets us know how they pulled it off with Scanline VFX’s V-Ray-based pipeline.

About Mathew Giampa

Mathew has over 16 years of experience in the visual effects industry as a compositor, compositing supervisor, and visual effects supervisor. He's worked on high-profile feature films including TRON: Legacy, Sucker Punch, Star Trek: Into Darkness, Justice League, and Aquaman, and served as visual effects supervisor on Joker, Black Widow, The Suicide Squad, and Cowboy Bebop. Mathew's work has been honored with VES nominations for Independence Day: Resurgence and Joker.

Want to know more about Mathew? He joined Chris on Chaos' CG Garage podcast to tell his fascinating and inspirational story.

#385: 2022-07-25 Subscribe

When did you decide to create the Aspen sequence digitally?

Mathew Giampa: The decision to create the sequence completely digitally was made early on in pre-production based on the scale of the effects for the sequence.

What are the pros and cons of working on a completely digital sequence?

MG: The benefits of working on a completely digital sequence are that it gives you complete creative freedom to change and manipulate things, from camera moves and lighting all the way to details within the environment to suit the creative needs for that specific scene, which is helpful for us to accomplish the director's vision.

In terms of negatives, replicating the realism and detail of such a large environment can be challenging and very time-consuming. It can also lead to images being more heavily scrutinized. There tends to be a misconception at times that something might look wrong when it's fully CG, even if the same thing happened in real photography. I've found that whenever possible, combining CG with live-action and real elements can give the best results but with less flexibility for changes.

How did you research and lookdev the anti-gravity effects?

MG: We looked at a lot of anti-gravity footage from space. Luckily, we have had experience with similar effects in past Roland Emerich films, such as the Singapore sequence in Independence Day: Resurgence. It was a similar approach and a good reference.

Could you tell us about recreating Aspen in 3D?

MG: For recreating Aspen, the client provided us with drive-through footage of Silverton (a nearby town in Colorado) as a base plan of the route they wanted, as well as reference imagery and drone photography of the buildings and the surrounding mountains.

After that, our 3D team, led by CG Supervisors Ashley Byth and Brian Grossart, combined the proxy Silverton Lidar with blocking out the route with a rough layout so we could get an early idea and buy off on the speed and distance we traveled. This also helped us establish which assets we would need to build in CG and at what quality, and how we would deal with extending Silverton into a bigger town and blending its aesthetic with Aspen.

We sent the client a top-down, super-rough camera view constrained to the car for the length of the sequence, so we could see where we would be in relation to the moon for every turn in order to have continuity with the gravity wave effects.

Once we had our core assets in place and our main manifest set up, we then scattered trees and props to fill out the streets before using snow piles created in Houdini to cover the city.

Where did you use Flowline in these shots?

MG: Flowline was used for our water simulations, fire, smoke, and some of the snow effects as well.

What was the biggest challenge here, and how did you solve it?

MG: The biggest challenge was the ability to render such large and ram-intensive scenes through V-Ray in a timely fashion so we can make adjustments where needed. This was solved with a combination of heavily optimizing scenes to be more efficient, as well as starting to use cloud computing with high memory machines for the most render-intensive shots.

Were there any changes to the shots from the studio? What techniques do you use to create rapid iterations?

MG: Like most projects, there are always changes to shots. A lot of pre-development at the beginning of the project goes a long way to give you the ability to create rapid iterations. What takes most of the time is creating the look. Once that has been established, you tend to have techniques that can be used on multiple shots, which makes for a quicker turnaround when changes are requested.

What are you most proud of here?

MG: I'm proud of how the team accomplished such amazing work on a large scale. It was great to work alongside CG supervisors Ashley Blyth and Brian Gossart, FX supervisors Amhad Ghourab and Michele Stocco, as well as compositing supervisors Ed Walters, Natalia de le Garza, and Dmitry Uradovskiy. They, along with the rest of the Scanline team, are truly amazing, and they give me the confidence that we can accomplish projects at such a huge scale and be proud of the work.