In this blog Ryan Grobins takes us through a detailed account of bringing his incredible short film Cyan Eyed to life. From humble beginnings to working with Skywalker Sound, this is a fascinating look of the entire process.

Introduction

My name is Ryan Grobins, originally from Adelaide, Australia, and I’ve been working in the VFX and animation industry for 25 years across six countries. I’m currently Head of CG at FuseFX in Vancouver, Canada where I enjoy being able to tackle big and small issues in order to produce high-quality images as efficiently as possible.

Professionally, my background in CG came from the path of lighting. I’ve been fortunate to be a part of some cool projects during my time in this industry, such as the Emmy award winning episode in the final season of Game of Thrones, Captain Marvel, Ant-Man & the Wasp, and much more.

I’ve made two animated short films previously that have done quite well on the festival circuit, playing in over 100 festivals combined and winning a number of awards. But I never like to do the same thing twice.

My first animated short film was a toon rendered adventure for children titled Sneeze Me Away, and my second film, The Rose of Turaida, was a highly stylised film made completely with sand like CG particles about a 16th century tragedy based on a true story set in Latvia.

Cyan Eyed

For my next film, I wanted to do something fun with a big spectacle, something as good, or even better than a cinematic from Blizzard or Blur!

Contrary to my previous two films, I aimed to release it publicly online when it was completed, rather than wait for one to two years while it was on the festival circuit, as many festivals demand exclusivity.

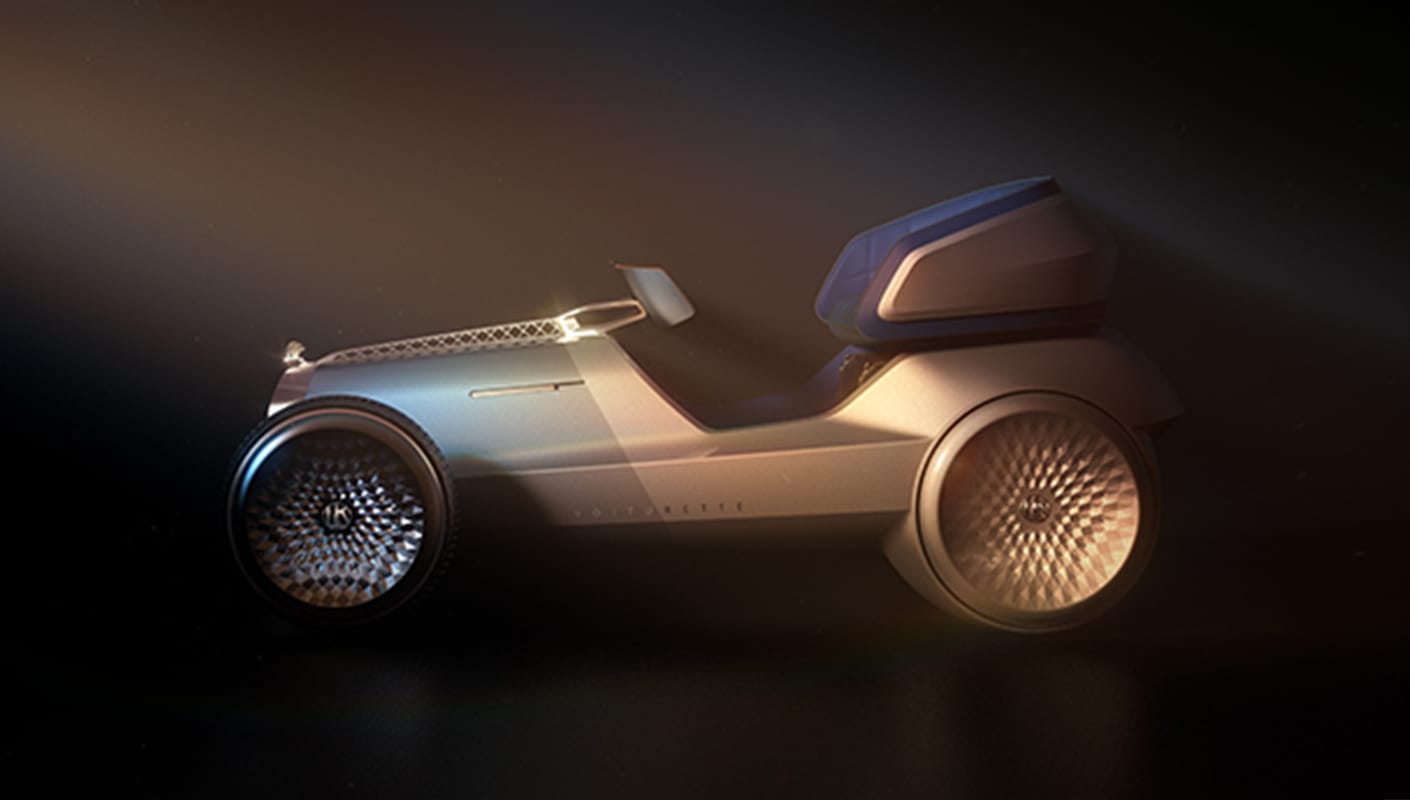

I’ve always loved steampunk, and from what I know of, there isn’t much of what I would call quality content in this genre, so I decided that I had a chance to contribute my own artistic interpretation.

Just after The Rose of Turaida started the festival circuit, I developed a relatively simple story outline of a robot rescuing a young girl from a bounty hunter pirate. After then coming up with the idea to give the young girl some sort of supernatural power, the film’s title, Cyan Eyed, was born.

The title is also an anagram of ‘eye candy’, and that is exactly what I wanted Cyan Eyed to be, a visual and aural feast for the eyes and ears. I knew I wouldn’t have the resources to go all the way for photoreal, and to tell the truth, I think photoreal can be a little limiting. I wanted more of a ‘hyperreal’ look, a style which allows for a some more artistic freedom, while retaining a high level of quality.

I was constantly finding ways to increase the quality of the film and as a result, this film took far longer to complete than what I originally had hoped for. But the result is exactly what I was after, as evidenced by the supportive comments it has received so far!

Altogether, there were a little over 50 people responsible for the visuals, and another 50 people responsible for the sound and music, definitely the largest team I have ever lead on a personal project.

As well as writer/direct/producer on the film, I was also an artist in every pipeline step. Of the 1679 asset and shot tasks on the film, I personally completed over 1200 of them myself, from previs to comp and everything in between.

I also wrote myself a new pipeline from the ground up, including file management tools, render submission and AOV management tools, texture, material, hair, cloth, animation and asset management tools, as well as a whole lot of ‘quality of life’ tools to make the workflow easier. Added up, over 10,000 lines of code went into this film!

Corona

How I found out about Corona can actually be attributed to a good friend and talented work colleague, Chris Pember. During a conversation I had with him in February of 2015, I mentioned that I was assessing different renderers to figure out which one I would use, but I really wasn’t happy with any of the options at the time.

I had been producing a few grey turntables of models using Mental Ray up until then, and Chris told me about a new renderer that had recently passed the 1.0 release that was being used in a number of arch-viz images. So I decided to give Corona Renderer a test using the trial, and I was instantly hooked.

The ease of use and the results in acceptable render times really appealed to me, as well as the physically based nature of it. Though I knew the decision was risky for a few reasons, this film was going to have human characters that I wanted to look as high quality as possible and volume effects like smoke and explosions, none of which was possible at the time in Corona, I mean it didn’t even have a layered shader!

Most of those features and more would come about two years later in v1.7, which I called the ‘VFX release’, and then continue to be added over the subsequent years. I stopped updating Corona versions after v5.0 as I had almost everything I needed then and I just wanted to finish the film and not have to redo any setups, also I was happy with the images I was producing.

To tell the truth, looking back now at the decision to use a new renderer to make an animated short film with the quality level of a high end game cinematic with only a fraction of the features other more mature renderers had at the time was wildly illogical.

But I have a tendency to prefer to use bleeding edge software, and I like staying ahead of the curve, and what I had read about the renderer and the devs at the time somehow gave me the confidence that everything was going to turn out alright in the end, and apart from one bug, it did.

The bug in question was that a camera could not be inside the bounding box of a VDB object, or else the object would disappear. I had to redo a couple of camera moves to get around this, but it wasn’t a big issue to do so.

Running through my favourite selected features that helped me out most of all were the following:

- v1.1 – Corona Bitmap map

- v1.2 – Displacement improvements

- v1.3 – Layered Materials, ‘Render Selected’ improvements

- v1.4 – Denoising

- v1.5 – Corona Materials improved to current PBR standards, LightMix

- v1.6 – ‘Terminator’ shading fix, prevent black appearance for lights

- v1.7 – (My favourite release!) Major render speed ups, hair shader, skin shader, SSS, CoronaBumpConverter

- v2.0 – VDB support, better motion blur

- v3.0 – CoronaMultiMap supporting ‘mesh element’ mode

- v4.0 – High Quality Image sample filtering, Adaptive Light Solver, motion blur support for Ornatrix

- v5.0 – Hair optimisations, renderer optimisations

Every static mesh for all assets in the film were converted to Corona Proxy objects (the Corona Proxy Exporter script was a huge help). This kept my Max scenes as small as possible on disk, as I had 141 shots in the film (as well as 5 trailer only exclusive shots), and being able to open up scenes as quickly as possible was a huge benefit.

For some objects like the skyship sails, I made use of an animated proxy object, simming a 500 frame sequence, then reusing it multiple times and giving each a little offset in time also helped keep my scenes as light as possible.

When v1.3 was released in November of 2015, most of the shaders that were made up until then were started from scratch, incorporating the new Layered Material node, though this wasn’t much work to redo, as look dev was still in the very early stages of development.

But when v1.5 was released almost a year later, another update to all the shaders had to happen, now that Corona was adhering to the industry standards of PBR, and I was now able to work effortlessly between Substance and Corona.

The results were much better than previous renders, and the shaders more or less stayed as is for the rest of the film. The skyship is made up of thousands of individual wooden planks all combined into a few proxy objects, and the thought of coming up with a complicated UV system to have each using a randomised wood texture from a set I had purchased was daunting. But then v3.0 finally released the life saving ‘Mesh Element’ mode in the CoronaMultiMap, and I was able to have a nice simple set up.

One feature in Corona that I did very much miss having was UDIM support, and my work around was to load in each texture manually for each type of input (albedo, glossiness, etc.), and hook them up by hand. This resulted in very large shader networks that were over 80% CoronaBitmap nodes connected to CoronaMultiMaps with the mode set to ‘Material ID’, and also needing to make sure that every single polygon had the correct material ID for it to all work properly.

This was a very tedious process, and it also locked me out of using material ID’s for anything else other than to replicate UDIM support, but I was still thankful for having figured out this method, otherwise, I wasn’t sure I had any other option. The UI for the Corona Material node was laid out in a very logical way, and I never had any problems with using it.

Another piece of the puzzle for necessary features was the CoronaBumpConverter node, as it was vital to be able to ‘bake down’ any sort of colour network to get the high quality desired look needed for the assets.

The final shading components that were vital for Cyan Eyed to look amazing were the hair and skin shaders that arrived in October of 2017. Both of these were modern implementations of the latest and greatest white papers in the industry. I’m not sure how much influence my many requests were to have these implemented at this time, but I’d like to think that I helped demonstrate how important they were.

One of the tools I am most proud of making was ‘Cyan Eyed Render Layers’, or ‘Cerl’ for short. This was a custom built render layer management tool that handled things like frame information, resolutions, cameras, object masking, light masking, farm submission attributes, AOVs and submitting passes to my farm.

While most of that is fairly agnostic to any renderer, the AOV management section I built into it was specifically made for Corona, and allowed me extremely easy access to manage any AOV for any shot, and have that data saved to disk so that I could edit it in a text file or copy render layer setups to other shots easily. I never needed to go to Corona’s ‘Render Elements’ tab in the ‘Render Setup’ global dialogue box to manually create, adjust or delete AOVs.

After many tests, I settled on a ‘Noise Level Limit’ of 8.0 with the ‘High Quality’ Denoiser set to the default values. While I needed high quality images, I was very mindful of the time it would take to render the whole film, and for that I set a ‘Time Limit’ as well to two hours and 40 minutes. The last little bit of help for reducing render times was to reduce the ‘Max Sample Intensity’ to ‘3.0’.

While most of the images were perfectly fine, some shots needed some extra denoising and filtering in Nuke, and in a very small number of cases where glossy reflective metallic surfaces had lots of motion blur, the fireflies were hand painted out. But I was ultimately very satisfied with the time vs. quality trade off.

The ‘Render Selected’ feature introduced in v1.3, last the last piece of the puzzle that allowed me to complete the main framework of the render layer system by combining my implementation in Maxscript of Houdini object masking. A lot render time was saved by being able to use any object as a matte object.

Corona was used to render everything except for the landscapes and the sky, which were made and rendered with Terragen. I also used Terragen to create HDRI’s that were used as the environment lighting for all Corona renders, internal and external.

I typically rendered the characters and skyship in separate passes for all the shots, along with an extra atmos pass for all internal shots.

One of the main reasons for choosing Corona was because it was so simple to use; I have never needed to fiddle around with render settings so little, unlike with every other renderer I have used, and I really felt like the devs listened to the community in regards to features and improvements.

I realise that my use of Corona for a VFX and animation heavy project is not the most common use, which I believe is for arch viz, I do hope that I’ve pushed the envelope of what can be done with Corona.

I set up and lit every shot in the film myself, and most of the film was rendered on my three computers: a Dual Xeon workstation that was rendering when I wasn’t working and two AMD Threadripper 2’s that rendered 24 hours a day for almost two years. They were great to have around during the winter time, and my wife often used the hot air exhaust to rise bread dough that she then baked.

When I was figuring out how I would render this film, I calculated that buying the components for the Threadripper 2 machines and building them myself would be cheaper than buying pre-made computers, because I really only needed a fast CPU and a decent amount of RAM, I didn’t need a good HDD or even a graphics card.

While it was a lot of money up front, it was far cheaper than if I had rendered most of it with an online render service, though I did use an online render service for a couple of milestone deadlines, like sound lock (which locks the edit to the point that the sound could safely be worked on. Cameras, sound & FX cannot change – but shaders and lighting can).

Sound

An epic steampunk themed animated short film needs an epic sound design so I took a chance in sending a cold email with concept art and a link to the latest Previs to the worlds best sound design company, Skywalker Sound.

I was very surprised when I received a reply telling me that they were very interested in being involved! I had two mix sessions at Skywalker Sound lasting about a week each almost a year apart, lead by supervising sound editor, Mac Smith. I can honestly say that being able to stay at Skywalker Ranch has been the highlight of my career so far, I was fully geeking out every minute of every day I was there.

Part way through production, my composer, Nicole Brady, gave me more amazing news: she managed to secure Peter Rotter, one of the most well known music contractors for major Hollywood films and the Hollywood Studio Symphony orchestra to contribute to Cyan Eyed.

I was able to attend the recording session in person at The Bridge, and was able to hear the music in all its full glory live!

My first two films took three years each, Cyan Eyed took more than double that time frame at over seven years. It was sometimes tough to keep up with the motivation to complete this film, there were many times where days or weeks went by without me moving the film forward, but thanks to a hugely supportive team, their work kept giving me inspiration to keep going.

Though I think what kept me going most of all is the thought of spending all this time and money, and not finishing the damn thing, in the words of Kamaji from spirited Away: “Finish what you started, human.”

In the end I am extremely happy with the result, and I hope my addition to the steampunk genre is something that fans of the genre are happy with, and I have Corona to thank for making it possible to render it all.

This film has been an amazing journey, and I am so glad to have the amazing team I did to make something that everyone can be proud of. Thank you for the opportunity to allow me to share the story of Cyan Eyed!

Synopsis

After years of searching, Grunt the automaton has finally caught up with the bounty hunter, pirate captain Corliss Vail, and its objective is clear – rescue the young, supernaturally gifted, Nessa Baelin from imprisonment on the bounty hunter’s skyship, and return her to Nessa’s father.

Links:

Official website

Twitter

Instagram

Artstation

Crew:

VISUALS

Ryan Grobins – Writer/Director/Producer/Asset Builder/Hair and Fur Technical Director/Look/ Development Artist/Texture Artist/Previs Artist/Animator/FX Technical Director/Lighting/Compositor

Albert Radosevic – Asset Builder

Andrew Krivulya – Hair and Fur Technical Director

Arthur Moody – Hair and Fur Technical Director

Artur Zima – Concept Artist

Benjamin Wheatley – Asset Builder

Benjamin Holen – Asset Builder

Brooks Kim – Texture Artist

Cary Graham – FX Technical Director

Christian Ronquillo – Concept Artist

Conor Schock – Compositor

Conrad Allan – Concept Artist

Conrad Murrey – Previs Artist

Curtis Carlson – Compositor

Damian Castellini – Animator

Daniel Alvarez – Concept Artist

Devon Gay – Compositor

Eddy Burnfield – Animator

Hyojung Kim Grobins – Concept Artist

Hugh Behroozy – Producer

Ivan Cadena – Animator

Ivo Šucur – Look Development Artist

Jacob Zaguri – FX Technical Director

Jasmin Watkins – Producer

Jennifer Kim – Texture Artist

Jessica Smith – Concept Artist

John Chen – Asset Builder / Previs Artist

John Toth – Texture Artist

Jonathan Romain – Look Development Artist

Joseph Leong – Animator

Joseph Roberts – Asset Builder

Kenji Gonzales – Concept Artist

Kim Allen – Animator

Matthew Zikry – Concept Artist

Matt McGrath – Animator

Melissa Olsen – Producer

Michael Plotnikov – Compositor

Michael Raiti – Animator

Ned Rogers – Concept Artist

Nick Beins – FX Technical Director

Nick Crowhurst – Associate Producer

Noemi Cini – Compositor

Paul Ziola – Animator

Phil Hook – Rigging Technical Director

Prateek Rangineni – FX Technical Director

Rahul Manoharan – Compositor

Rana Kar – Animator

Robert Paternoster – Animator

Samuel Collins – Animator

Sean Watts – Public Relations Manager

Sheree Chuang – Texture Artist

Stanley Darmawan – Animator

Tanya Philipsen Jørgensen – Motion Graphics Artist

Victor Mahnic – FX Technical Director

Yucheng Hong – Concept Artist

Zoran Dragaš – FX Technical Director

SOUND

Mac Smith – Supervising Sound Editor

Nathan Nance – Re-Recording Mixer

Brandon Proctor – Re-Recording Mixer

Luke Dunn Gielmuda – Foley Editor

John Roesch – Foley Artist

Scott Curtis – Foley Mixer

John “JT” Torrijos – Projectionist

Jim Austin – Engineering Services

Ivan Piesh – Digital Editorial Support

Jessica Engel – Post-Production Sound Accountant

Michael Peters – Post-Production Finance Manager

Eva Porter – Client Services

Carrie Perry – Scheduling

Josh Lowden – General Manager

Jon Null – Head of Production

Steve Morris – Head of Engineering

MUSIC

Nicole Brady – Composer

Tristan Coelho – Music Editor

Milton Gutierrez – Recording and Mix Engineer

Peter Rotter – Contractor and Conductor

Tim Ryan – Supervising Music Editor and Mix Engineer

Elaine Beckett – Trackdown Producer

Bob Scott – Mastering Engineer

Rob Brophy – Viola

Zach Dellinger – Viola

Brian Dembow – Viola

Alma Fernandez – Viola

Shawn Mann – Viola

Matt Funes – Viola

Darrin McCann – Viola

Victor DeAlmeida – Viola

Laura Pearson – Viola

Erik Rynearson – Viola

Andrew Shulman – Cello

Tim Loo – Cello

Jacob Braun – Cello

Erika Duke – Cello

Dennis Karmazyn – Cello

Mike Valerio – Bass

Ed Meares – Bass

Ben Jaber – French Horn

Teag Reaves – French Horn

Steve Becknell – French Horn

Laura Brenes – French Horn

Alex Iles – Trombone

Bill Booth – Trombone

Phil Keen – Trombone

Craig Gosnell – Trombone

Lachlan Colquhoun – Electric Guitar