Are you looking for some tips on how to improve your next render? Nikos Nikolopoulos shares his expert advice on how to bring the wow factor to your project.

What do you see when you look into the light? I see life, growth, emotions, intertwined stories, and a call for creative adventure! For the past eight years, I have made it my mission to help architects, designers, and visualization studios transform their creative vision with photorealistic images that captivate and inspire with the power of light.

In this article, I’ll reveal five artistic principles to help you become a better CG artist and take your work to the next level.

About Nikos

Nikos Nikolopoulos has risen to the top of his industry as a creative director and educator. His editorials have appeared in ArchDaily, Dezeen, and 3D World Magazine. He has taught some of the world’s top architects, designers, and visualization studios, including Foster + Partners, Make Architects, Perkins & Will, Kilograph, Pureblink, and more. His unique cinematic approach to lighting is shared in the CG community globally through masterclasses, workshops, and live events.

1. Explore creative lighting

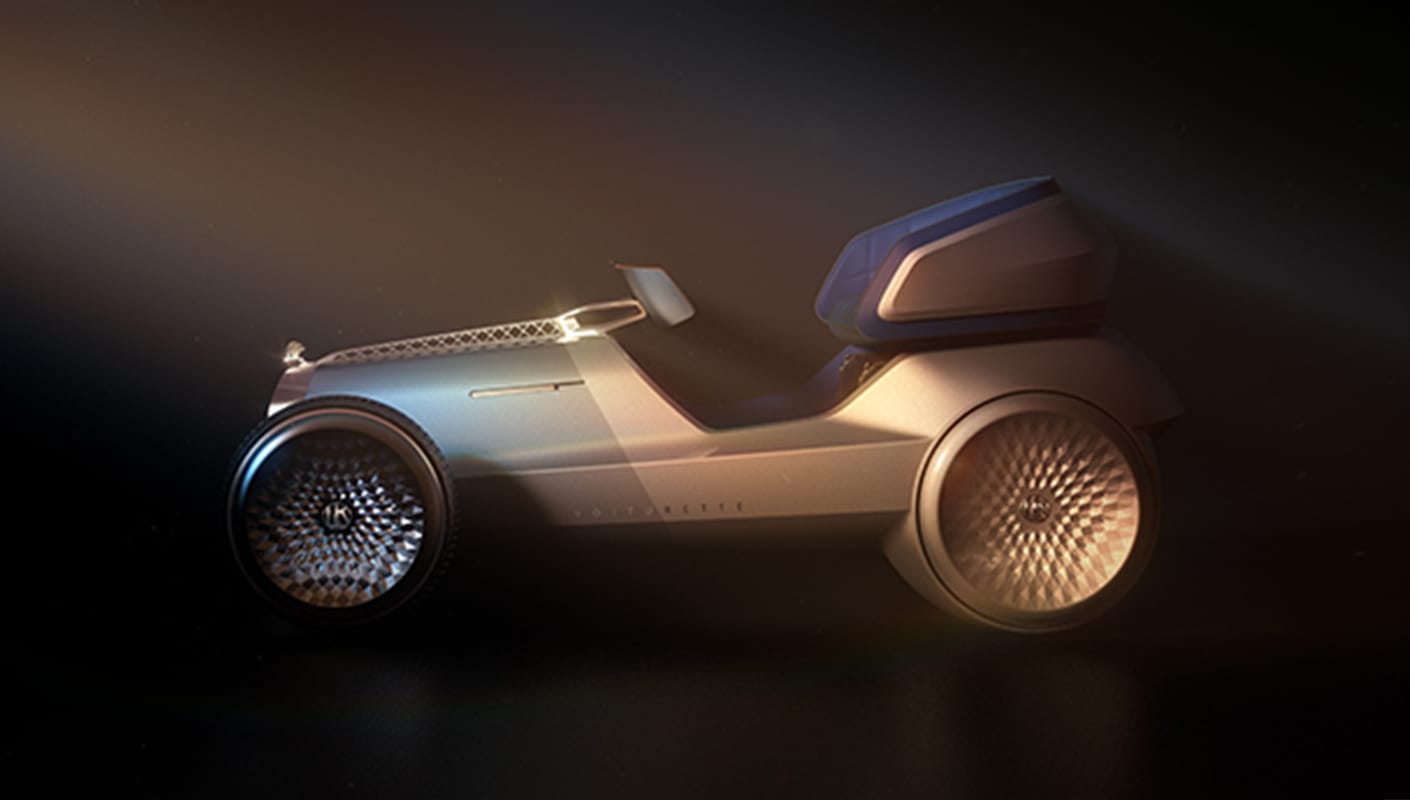

“You don’t take a photograph, you make it,” said the great American photographer Ansel Adams. The idea that photography is ’truth’ is a powerful and wildly held misconception that you need to break free from. Look at the number of lights professional photographers use for an interior, car, or portrait shoot. Try to find images of the lighting setups for scenes from films that you admire. Seeing photography as something constructed is the first step to understanding the creative potential of photorealistic rendering.

Use lights as a painter would. Put them where you want the viewer to look and remove them where they’re not helping to clarify what you want to say. Experiment with the balance of your lights, and test their temperature and hierarchy. Think about light, message, and composition as one thing. Good CG artists avoid dull and dutiful realism — just like good photographers.

2. Diversify your sources of inspiration

Creating images is not always the easiest way to make a living, although it can be a deeply rewarding one. Staying inspired has to be worked at.

Think of inspiration as a jug. What goes into that jug is very personal. It might be Danish furniture design, modernist literature, fashion photography, or 1970s concept art. As an artist, it’s vital that you keep filling this jug. Look outside your immediate CG rendering world for sources of inspiration. You will only truly find your artistic voice by chasing down the things that really move you.

When you come to create your own work, you simply need to pour out a little from the jug. Even on what may seem like a dull job, there’s always space for trying something new, pushing boundaries, or finding beauty.

3. Practice critical observation

Look critically at photography. Like all visual art forms, it has its languages, subtleties, and discourses. Watch films to learn about creative lighting. Look at the early pioneers of black-and-white photography to learn about composition. Take your own photographs. The wider your awareness of what photography has achieved, the greater the potential there is for your own CG work. If you can’t imagine it then you can’t make it.

Look at light. Hopefully, you have had the experience of being literally stopped in your tracks by some unexpected and uncommonly beautiful behavior of light, only to realize the people you are with have not seen it. If not, look harder.

4. Have a clear direction

The temptation with any image is to just start. But be careful: this can lead to wasted hours and weak images. Before you start, you need to be clear about the direction of the image and let this guide every creative choice.

Always start with a clear brief and you may have to push a client to articulate what it is they want to say. For personal work, clarify your thinking. Strong art says one or two things clearly; immature art tries to talk about everything.

You should also gather visual references. Mood boards are the first step in the transition from words to pictures. They help define a quality of light, a color palette, or a mood. They can also help you explore the context and visual history of your ideas. You have the whole of the world’s history of design and image-making to draw upon. Inspiration can be found in unlikely places.

5. Form a strong composition

How many photographs are taken every day in, say, London? A lot. How many are truly great? Very few. What elevates those few is the clarity of the message and refinement of composition.

Composition is the hidden language: the patterns of shape, the interplay of light and dark, the use of line and color. To learn more about composition, study the work of great artists critically. How have they used restless diagonals to evoke the breathless confusion of battle, tonal patterns to force your eye to a focal point, and colors to tell you about the emotional state of the subject? Some find composition easy. Others have to really work at it.

So you may be wondering, what exactly led me to collect these artistic principles and put them into practice?

The story of Creative Lighting

I developed Creative Lighting while working as a CGI director at Cityscape Digital in London. I worked closely on the concept together with Damian Fennell, the creative director of Cityscape, and we launched the brand in 2015. Our passion for lighting and a desire to produce beautiful, exceptional images led us to create Creative Lighting.

To begin with, we explored the cinematography world for inspiration and spent a year analyzing films, especially the work of Roger Deakins. After extensive research, Pinterest boards, sketches, and many 3D tests, an in-house workshop was born: Creative Lighting vs. Mundane Realism. From there, the philosophy took on a life of its own.

What we believe in

Creative Lighting is a philosophy of image-making that sees light as the primary force in imagery. It’s about learning to see and think about light as a photographer or cinematographer does and the craft of image-making as a painter would. It is an approach to image-making that favors the artist’s vision over technical knowledge.